Very often, expressive individualism is the hidden dogma behind the most controversial questions of our age, whether it be social justice, abortion, sexuality, marriage, genetic engineering, or assisted suicide. It is essentially the notion that the human self reigns supreme, that we are our own individual standards of meaning and morality, and that we have a moral duty not to follow our Creator but to follow our hearts. This dogma did not magically pop into existence but was crafted by many thinkers, evoking the question: How well did a life of expressive individualism pan out for those who pioneered it as an ideology? Let’s get to know some of these pioneers.

It sounds like it was written yesterday, but two-and-a-half centuries ago Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-78) said, “All I need to do is to look inside myself.” His goal was to “make known my inner self, exactly as it was in every circumstance of my life,” making him a forefather to the stream-of-consciousness emotional broadcasting found throughout today’s blogosphere and social media. With an eye toward his own freedom and self-expression, he abandoned all five of his children to early deaths at an orphanage.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) taught that “Egoism is the very essence of a noble soul.” After a deeply lonesome life, Nietzsche spent his last decade on earth in an asylum, known for dancing naked, fantasizing about shooting the Kaiser, and believing himself to be Jesus Christ, Napoleon, Buddha, and other historical figures.

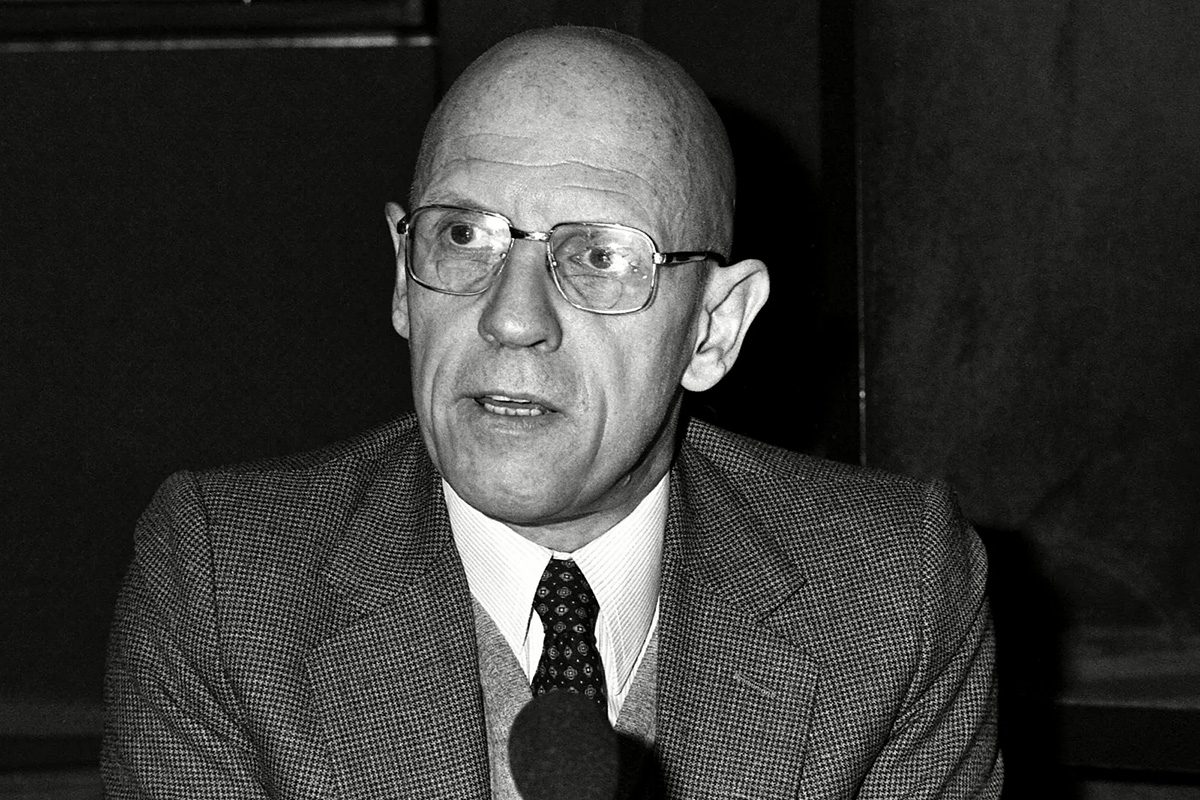

Michel Foucault (1926-1984), a devotee of Nietzsche, saw sexual experiences as the path to self-glorification, calling us “to exchange life in its entirety for sex itself, for the truth and the sovereignty of sex.” He battled suicidal tendencies most of his adult life. He argued for “consensual” sexual relations between adults and children, campaigning for the legalization of pedophilia in France. When relocated to Berkeley, Calif., Foucault threw himself into the sadomasochistic homosexual scene. Sadly, he contracted HIV/AIDS and, like Queen’s Freddy Mercury, continued to gratify his sexual appetites even after he knew he was infected. When Foucault said, “Sex is worth dying for,” he practiced what he preached, not only for himself but for unsuspecting others.

Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) added an occultic element to expressive individualism, inventing a religion called “Thelema” (from the Greek noun for will, want, and desire). Crowley distilled the dogmas of his faith to Hamlet’s credo, “Do what thou wilt.” He expounds, “Only you can ascertain your own True Will; no god, no man, no institution or nation surpasses your Holy Authority over yourself.” His biographer described him as “brash, eccentric, egotistic, highly intelligent, arrogant, witty, wealthy, and, when it suited him, cruel.” In doing what he willed, Crowley became a heroin addict, physically assaulted his lovers (male and female), and appreciated both Nazism and Communism for their deeply anti-Christian themes.

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) was a forefather of expressive individualism with his doctrine that “man is nothing else but what he makes himself.” We exist in a Godless universe and it is, therefore, totally up to us to invent our own essences. What did Sartre make of himself? He was known as a vast ego and notorious womanizer, with a revolving door of mistresses he famously treated more like prey than persons. It wasn’t about “physical pleasure,” for Sartre, “it was about the thrill of the chase, the almost sadistic conquest of another.” He got hooked on amphetamines, hid Vodka behind his books to help him get blackout drunk, and talked often with imaginary visitors. Hardly the poster boy of boundless freedom he had advertised to a generation of adoring youth, he confessed, “I’m gaga, as they say. Or, I’m not stupid. But I’m empty … there are not many things left that excite me.”

I have not cherry-picked the least flattering cases. Read up on the personal lives of others saints of expressive individualism—Marquis de Sade, Alfred Kinsey, Jim Morrison, L. Ron Hubbard, Wilhelm Reich, Jacques Derrida, or others. We know a tree by its fruits and the fruits of these men’s lives should be enough to give us pause before we embrace their calls to be true to ourselves.

Our task is to be true to Christ—and bring the self into obedience to the Savior.